AI has always felt economically different from other software systems. I never assumed inference costs would quietly fade into the background, and I also never saw a clear path for that happening in the short to mid term. Still, what surprises me is how many large bets are being placed on the opposite assumption, with pricing models that have barely evolved.

To be clear, I’m not saying this is guaranteed forever. Hardware can improve. Model architectures can change. Someone might invent a dramatically more efficient way to “think” that doesn’t burn tokens like a candle in a wind tunnel. If that happens, the economics could look very different. For now, though, based on what I’ve seen over the last year or two, scaling AI products still feels structurally unlike scaling a typical SaaS product.

TLDR

- Traditional software likes scale because marginal costs tend to drop. In contrast, AI usage often keeps a real meter running.

- As a result, your most valuable users can become your most expensive users because they trigger deeper reasoning, longer flows, retries, and tool calls.

- Although people argue about input vs output tokens, the bigger issue is token behavior over time: context grows, loops happen, and cost compounds.

- In particular, agents create “self-feeding” workflows where output becomes input repeatedly, which can inflate cost even if the user only asked one question.

- Meanwhile, token prices are dropping in some ecosystems, especially in China. However, cheaper tokens don’t automatically fix flat pricing when usage is unbounded.

- On top of that, customers usually want the newest “best” model tier, and that tier is rarely the cheapest tier.

- Prompt engineering, context engineering, RAG, memory, and tool calling all help quality, yet they also tend to increase tokens, which pushes costs up.

- Finally, local inference is my favorite structural escape hatch because it shifts marginal cost from your servers to the user’s device, and I expect local AI to consolidate into OS-level APIs.

Why AI economics feel different in practice

In most software products, scale is your friend. More users can mean better utilization, stronger amortization, and more opportunities to optimize. Over time, that usually pushes average cost per user downward, which is why classic software can improve margins as it grows.

AI behaves differently. Once usage becomes meaningful (not demos, not curiosity clicks, but real reliance), cost does not politely smooth out. Instead, it becomes more visible, more variable, and sometimes more aggressive as users extract more value. In other words, the product gets stickier and the bill gets louder.

Now, could this change? Potentially. If inference becomes radically cheaper due to better hardware, better kernels, new distributed architectures, or model designs that need fewer tokens to reach the same quality, then the marginal cost curve could flatten. Still, betting your unit economics on that breakthrough arriving exactly when you need it is risky. As a result, I treat today’s economics as a constraint, not a temporary inconvenience.

The flipped reality of inference: your best users cost the most

In older software, your best customers were typically your best margins. They paid reliably, churned less, and made your support time worthwhile. With AI, however, the relationship can invert.

Your most engaged users often:

- ask harder questions,

- run longer workflows,

- demand more thoroughness (“think harder”),

- trigger retries and self-corrections,

- and push into tool calling.

Because of that, they generate the most compute. So instead of “more usage → more margin,” you can end up with “more usage → more cost.” That inversion alone should make anyone cautious about flat pricing.

Of course, you can add rate limits, degrade experience, or push heavy users into higher tiers. However, notice what those strategies represent: they’re basically ways of reintroducing usage-based economics, only more awkwardly. Therefore, even if you can delay the problem, you still have to price around it eventually.

Token costs aren’t the point, inference behavior is

A lot of discussions get stuck on whether input tokens or output tokens matter more. In practice, it depends, and that’s exactly why the debate is a dead end.

Sometimes you send massive context and get a short answer. That’s where context engineering shows up: RAG, memory, user history, policies, customer profiles, product docs, and so on. In those cases, input dominates. At the same time, the work you did to get a better answer was literally “make the input longer,” which is great for quality and also great for cost.

Other times, the context is moderate, yet output explodes because the model reasons, plans, calls tools, retries, reflects, and generates intermediate work. Output tokens are often priced higher than input tokens, and thinking tokens frequently live on the output side. OpenAI explicitly notes that reasoning models generate reasoning tokens, those tokens take up context, and they’re billed as output tokens (https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/reasoning). Consequently, you can pay a lot of output even when the user only sees a short final message.

This is where prompt engineering and context engineering become a recurring tension. You can squeeze more intelligence out of the system by crafting better prompts, adding better memory, and retrieving better documents. However, you’re usually doing it by increasing tokens. Meanwhile, if the context gets too long, the model can actually get worse at using it, so you’re balancing intelligence and cost at the same time. That balance is hard, and it gets harder as products get more agentic.

Where things really break: agents and self-feeding loops

The real multiplier isn’t “prompts.” It’s agents.

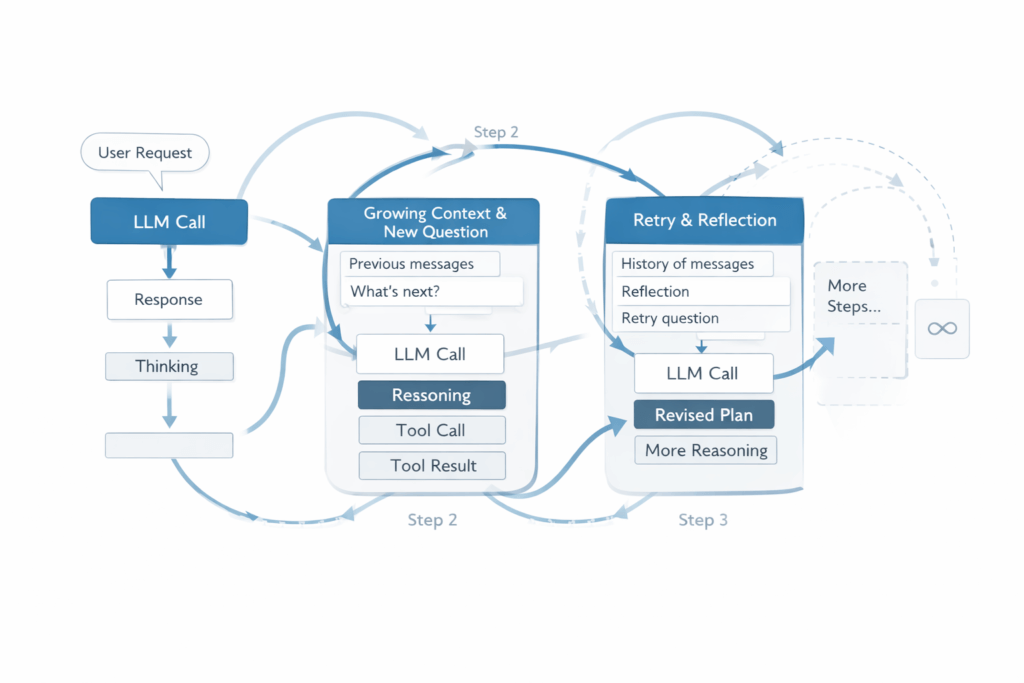

Agent systems don’t operate in a single pass. Instead, they plan, execute a step, inspect results, reflect, retry or refine, and repeat. In many designs, the output of one step becomes part of the input of the next. Then the next step creates more output. Then that output feeds the loop again. Therefore, cost compounds quietly.

This matters because the user didn’t necessarily request more messages. The system decided to keep going until it felt confident. As a result, you end up paying for intermediate work, not just the final answer. Google even notes that some agent-style features can bill standard token usage for intermediate tokens during the process (https://ai.google.dev/pricing).

Now, could agent systems become dramatically more efficient? Possibly. For example, better planning, better stopping criteria, or architectures that reuse computation more effectively could reduce the need for retries and reflection loops. Still, today’s mainstream agent patterns often “spend tokens to buy reliability,” which is exactly why fixed pricing starts leaking badly once usage becomes serious.

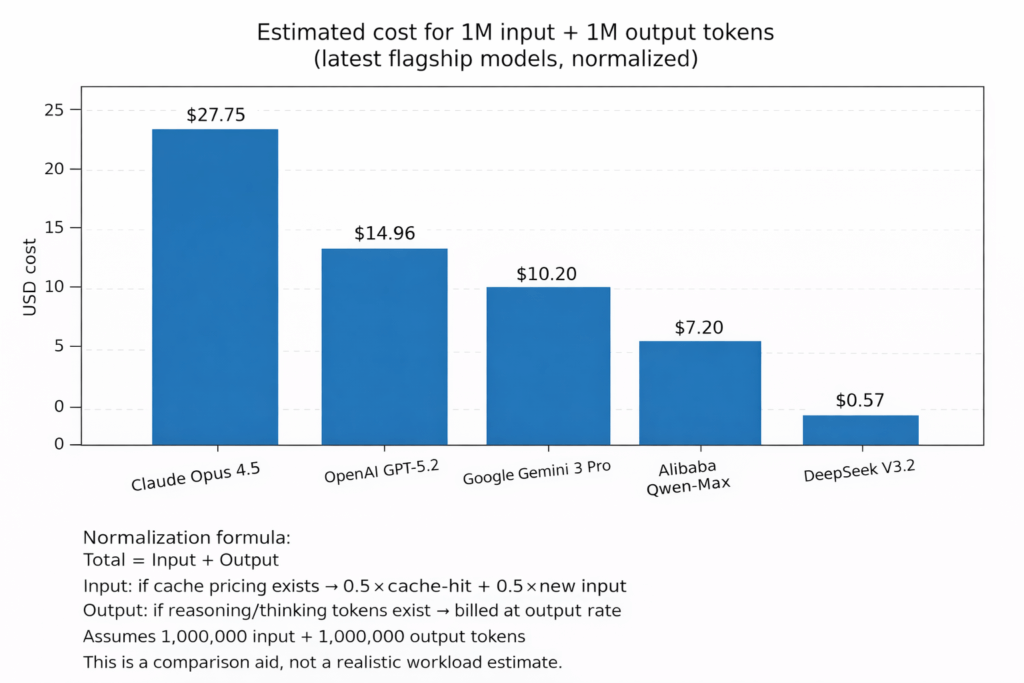

A quick look at current flagship inference pricing

To ground this in reality, here are current list prices pulled directly from public pricing pages. These numbers aren’t moral judgments. They’re context. Also, pricing changes frequently, so if you’re reading this in the future, consider these snapshots rather than eternal truth.

How the comparison chart is normalized

The chart uses a deliberately simple normalization:

- Assume 1,000,000 input tokens and 1,000,000 output tokens

- If the provider offers discounted cached input pricing, assume 50% cache hit and 50% fresh input

- If the provider distinguishes “thinking/reasoning,” assume half the output is “thinking,” but billed at the output rate unless stated otherwise

This isn’t a realistic workload estimate. Instead, it’s a comparison aid.

A few flagship examples (official sources)

- OpenAI’s API pricing page lists GPT-5.2 at $1.75 / 1M input, $0.175 / 1M cached input, and $14 / 1M output (https://openai.com/api/pricing/).

- Anthropic’s pricing page lists Claude Opus 4.5 at $5 / MTok base input, $0.50 / MTok cache hits, and $25 / MTok output (https://platform.claude.com/docs/en/about-claude/pricing).

- Google’s Gemini pricing page lists Gemini 3 Pro Preview with per-million rates, including context caching, and notes that output pricing includes thinking tokens (https://ai.google.dev/pricing).

- DeepSeek publishes per-million USD pricing with separate cache-hit and cache-miss input rates plus output rates (https://api-docs.deepseek.com/quick_start/pricing-details-usd/).

- Alibaba Cloud Model Studio publishes Qwen pricing by tier and region, and separately describes context cache billing rules (https://www.alibabacloud.com/help/en/model-studio/model-pricing and https://www.alibabacloud.com/help/en/model-studio/user-guide/context-cache).

The gap is obvious. In some cases, per-token prices differ by an order of magnitude. Importantly, that difference is real pressure, and it’s not just theoretical anymore.

However, the structural issue doesn’t disappear just because tokens are cheaper. If usage can expand without bound, cheap tokens can still accumulate into meaningful cost. Moreover, if agents loop freely, cost grows regardless of unit price. So while price competition matters, it doesn’t automatically solve flat pricing.

How $20 per month became the anchor

Early consumer AI pricing set expectations that still shape the market today.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT Plus is listed at $20/month (https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6950777-what-is-chatgpt-plus). That price point became an anchor. Once people internalize “AI is a subscription,” they stop thinking in metered terms. Instead, they expect “unlimited-ish” usage, even if nobody says the word unlimited.

There were also early reports of higher price exploration, commonly cited around $42/month, including coverage from PCMag AU (https://au.pcmag.com/news/98401/not-cheap-paid-version-of-chatgpt-costs-42-per-month) and other outlets discussing the same idea (https://gizmodo.com/openai-chatgpt-plus-price-20-42-per-month-1849991110). Whether that was formal A/B testing or early market probing, the result is the same: the consumer market got trained on a monthly anchor before the world had good intuition for agent loops, tool use, and how fast token usage could grow per user.

Could that anchor be unwound? Yes, in theory. Platforms could introduce usage tiers, add hard limits, or charge for heavy usage. Still, expectations are sticky. Therefore, even if the economics demand change, the transition is painful.

Why cheaper models don’t fix fixed pricing (especially when users demand the best)

Cheaper tokens help. They reduce pressure, widen access, and make experimentation easier. Yet they don’t fix the core problem.

If pricing is flat and usage is unbounded, heavy users get subsidized by light users until the math stops working. Even worse, agent loops can make “usage” feel detached from the user’s intent. So the cost can grow even when the user believes they’re doing something simple.

There’s another issue that feels obvious once you’ve lived it: the newest flagship model is rarely the cheapest model, and customers tend to ask for the newest flagship anyway. You can choose to sit on older models, and sometimes that’s a great strategy. However, you’re competing in a market where “better intelligence” is the feature, so demand keeps pulling you upward.

Meanwhile, all the techniques we use to squeeze more quality out of models often increase tokens:

- RAG adds retrieved documents into the prompt, which increases input tokens.

- Memory systems add user history, preferences, and summaries, which increases input tokens.

- Tool calling increases output tokens (planning and calling) and can increase input tokens (tool results and history).

- Retry and reflection patterns inflate both sides.

So even if prices per token are falling, tokens per task can rise, especially as product expectations shift toward “do it reliably” instead of “answer quickly.” Consequently, “cheaper tokens” doesn’t guarantee lower spend in a real product.

Local inference is my favorite direction (but it’s not magic)

Local inference doesn’t make AI free. It just moves the bill. Instead of you paying for every extra “think step” in the cloud, the user pays with electricity, battery, thermals, and hardware cycles. That shift matters because it **democratizes the cost structure**. In the cloud, a handful of heavy users can quietly become your margin problem. On-device, heavy usage still costs something, but it stops automatically turning into *your* burn rate.

What makes this direction interesting is how quickly the prerequisites are improving. Smaller models get more capable every year, and consumer hardware keeps getting better. We already run surprisingly useful models locally on laptops and, increasingly, on phones. Right now the tradeoffs are obvious (latency, battery drain, heat), but those constraints feel like moving targets, not permanent walls.

If local inference becomes “good enough” for a large chunk of everyday tasks, it also unlocks a different kind of product design. Instead of pricing your product around token consumption, you can price around what you actually add: better agent workflows, better tooling, better UX, better integrations, and better outcomes. In other words, builders can compete on *value* without needing to subsidize *compute* every time the user clicks “try again.”

Could cloud inference still dominate frontier reasoning? Absolutely. If hardware stalls or if local models plateau, cloud will keep winning the hardest tasks. Still, for privacy, offline reliability, and scalable ecosystems, local inference looks like the most structurally sane layer we can add to the stack.

My prediction: local AI becomes an OS primitive (like GPS, camera, or dictation)

I don’t think the future looks like “every app downloads its own giant model.” That path creates storage chaos, duplicated runtimes, constant updates, and a nightmare permission story. Instead, I expect consolidation: platform owners will ship local models and expose them through OS-level APIs, with a consistent permission model and clear resource controls.

This isn’t a new pattern. Apps don’t ship their own GPS stack. They request location from the OS. Apps don’t ship their own secure storage. They use the keychain. Even better: most apps don’t ship their own text-to-speech engine or dictation system. They call the OS speech stack and move on.

I think local AI follows the same arc. Apps will “use the AI of the device” the way they use the camera or dictation. That’s not just a prediction from vibes either. We already see early signs:

- Android ML Kit GenAI (Gemini Nano / AICore): https://developer.android.com/ai/gemini-nano/ml-kit-genai

- Apple newsroom (Foundation Models framework): https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2025/06/apple-intelligence-gets-even-more-powerful-with-new-capabilities-across-apple-devices/

- Microsoft Windows AI API (Phi Silica): https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/ai/apis/phi-silica

Once that OS layer stabilizes, the really interesting thing becomes possible: personal, one-to-one local AI that doesn’t feel like “the same cloud model with different prompts.” A local assistant can accumulate durable personalization, and it can potentially adapt over time while idle through lightweight tuning, preference learning, and private memory systems. At that point, the user’s AI becomes an asset. If you lose it, you don’t just log in somewhere else and get the same thing back.

This direction could still stall. Hardware limits, fragmentation, platform incentives, and privacy policy all matter. However, if the OS vendors keep pushing local AI as a native capability, the economics change in a way that cloud pricing alone can’t replicate.

Closing thoughts

AI pricing isn’t broken because models are expensive. It’s broken because usage scales in ways fixed prices struggle to absorb, and agentic systems make that mismatch impossible to ignore.

Yes, tokens get cheaper over time in some ecosystems. Yes, competition from cheaper providers matters. However, as long as customers keep demanding the best models, and as long as we keep squeezing more quality through prompt engineering, context engineering, RAG, memory, tool calling, and retries, token volume tends to climb. That’s why scaling AI under flat pricing often feels backwards: the best users create the most value and also generate the most cost.

None of this is permanent law. If someone invents an architecture that compresses “thinking” without token waste, or if new hardware makes inference dramatically cheaper, the shape of this problem could soften. For now, though, the constraints are visible enough that it feels irresponsible to ignore them.

If pricing evolves to reflect how AI systems are actually used, margins can become sane again. Until then, pretending AI behaves like classic SaaS just delays the adjustment. And personally, I keep coming back to the same preference: local AI and edge inference look like the most structurally sane path, because they redistribute cost and improve privacy at the same time.

Sources

- OpenAI API pricing: https://openai.com/api/pricing/

- OpenAI reasoning tokens guide: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/reasoning

- Anthropic Claude pricing: https://platform.claude.com/docs/en/about-claude/pricing

- Google Gemini pricing: https://ai.google.dev/pricing

- DeepSeek pricing details (USD): https://api-docs.deepseek.com/quick_start/pricing-details-usd/

- Alibaba Model Studio pricing: https://www.alibabacloud.com/help/en/model-studio/model-pricing

- Alibaba context cache rules: https://www.alibabacloud.com/help/en/model-studio/user-guide/context-cache

- ChatGPT Plus $20/month: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6950777-what-is-chatgpt-plus

- PCMag AU $42/month mention: https://au.pcmag.com/news/98401/not-cheap-paid-version-of-chatgpt-costs-42-per-month

- Gizmodo coverage of $20 vs $42: https://gizmodo.com/openai-chatgpt-plus-price-20-42-per-month-1849991110

- Android ML Kit GenAI (Gemini Nano / AICore): https://developer.android.com/ai/gemini-nano/ml-kit-genai

- Apple newsroom (Foundation Models framework): https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2025/06/apple-intelligence-gets-even-more-powerful-with-new-capabilities-across-apple-devices/

- Microsoft Windows AI API (Phi Silica): https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/ai/apis/phi-silica